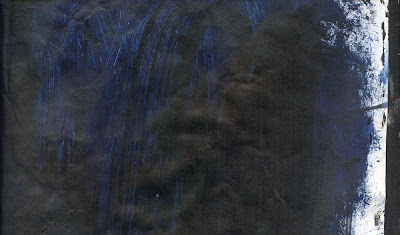

James Whitney Lapis 1966

The Whitney Brother's John (1917-95) and James (1921-82) were key pioneers of independent American animation. They were important “for laying the groundwork for the whole field of computer animation and digital special effects” (Beck, 2004 p. 216).

John Whitney studied 12-tone music and animation of abstract design in Paris in 1937-38. On returning to the United States he joined his brother James who was a painter and produced their first film, Twenty-Four Variations (1940) an 8mm abstract film that used circles and triangles. For the production John Whitney built his own optical printer. From 1940-45 they produced five abstract film exercises. John Whitney significantly created sound directly onto film, a technique later developed by Norman McLaren

John Whitney went on to found Motion Graphics, Inc in 1952 to produce commercial films. Then he moved to the UPA to become a director in 1955 and then worked at the

In 1959 John Whitney began to use a World War II gun sight (designed by Norbert Wiener?) which essentially was a simple analogue computer, to help produce simple visual effects (Beck, 2004 p. 216)..

The film Lapis, “is named after the philosophers stone in practice of alchemy and encourages notions of contemplation and a fuller understanding of the place of humankind with the cosmos” (Wells, 1998 pp. 30-31).

Sources:

Beck, J., (2004) Animation Art: From Pencil to Pixel, The History of Cartoon, Anime and CGI London: Flame Tree Publishing.

Wells, P., (1998) Understanding Animation London and New York: Routledge

Further reading:

LeGrice, M. (1977) Abstract Film and Beyond, Cambridge, Mass and London: MIT Press.

Russett, R., and Star, C., (1976) Experimental Animation: An illustrated Anthology New York: Van Nostrum Reinhold.

John Whitney Sr. Homepage: http://www.siggraph.org/artdesign/profile/whitney/whitney.html