Sunday 28 February 2010

Thought of the Semester

Arthur C. Danto quoted by Paul Guyer in a review of Danto's The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art, New York: Columbus University Press 1986 in New York Times, Feb 2, 1987 p.23.

Saturday 27 February 2010

László Moholy-Nagy

"The Theatre of Totality with its multifarious complexities of light, space, plane, form, motion, sound, man – and with all the possibilities for varying and combining these elements – must be an ORGANISM."

"Theatre, Circus, Variety, " Theatre of the Bauhaus (1924)

Thursday 25 February 2010

Digital Culture: 5

According to Baudrillard reality has disappeared: we live in an age of simulation. It is an age where "truth, reference and objective cause have ceased to exist". The very "spectre of simulation" threatens the distinction between "true" and "false" (Baudrillard, 1983 p.6). Expanding upon the idea Baudrillard stated that "it is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology), but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real" (1983, p. 25)

Baudrillard, J (1983) Simulations Semiotext(e)

See also Eco, U Travels in Hyperreality

Tuesday 23 February 2010

A Beautiful Blog: The Art of Memory

The Art of Memory

Richard Diebenkorn

Heidigger once described the brush stroke as an abyss suspended above the form. Derrida used this description to describe the line (Gilbert-Rolfe, 1995, p. 87).

gouache on paper

I have mentioned Diebenkorn once in a post in terms of the colour I applied to a painting that I subsequently scanned. The mixing of lamp black and Prussian blue is a mix of of colours used by Cezanne and Diebenkorn. Gilbert-Rolfe compared Diebenkorn to Cezanne and described the bluish black used by the two artists as the "deepest and most unfathomable colour available to the imagination, the colour of the night sky, colour of the bottomless pit" (1995 p. 87). Gibert-Rolfe in his description of Diebenkorn Ocean Park drawings describes the lines as having a depth that is atmospheric and "a fathomlessness of blackness presented in the line". He goes on to say that the line acts as a "boundary " that "subdivides and organises through subdivision the uncertainty of atmosphere- as in the case with both drawing and writing in general, blackness bringing meaning to whiteness, night organizing day" (p. 90)

Sunday 21 February 2010

Cyberwar and Peace

We may think of war as being physical and throughout history we see in battles the use of conventional weapons: swords, guns and bombs. The programme argues that the conventions of warfare had not really changed between the times of Julius Caesar and the Battle of Waterloo. Mechanization of the military revolutionised war in the 20th Century radically changed the nature of conflict, yet today, it is not just the nuclear deterrent or new missile weapons systems that protect us from attack, but also the computer and its protection software. The attack comes from a hacker whose aim is to disrupt communication and information systems. This may seem the stuff of science fiction and thrillers (one thinks of films like Hackers or The Net, both from 1995), but these attacks are a regular occurrence. During the late nineties the conflicts in Kosova and Bosnia, America’s military industrial complex and many universities (MIT was one victim) were hacked by the Serb secret service and Serbian students.

Recently, the US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton delivered a speech on how the internet can spread freedom around the world. It has been seen as a response to Google’s withdrawal from China due to alleged cyber attacks on human rights activists. Before Clinton made her speech, Robert Amsterdam, a lawyer specialising in cases against repressive governments, and Tom Watson MP, discussed how the internet is used by rogue governments on the Today programme, Radio 4. Tom Watson raised the problem in House of Commons.

Robert Amsterdam agreed with the idea of the web being used to “promote freedom” and supports Google’s position. He also proposes that “we” should monitor the ways in which oppressive governments use the web to stifle debate and free expression and also notes how Western companies and multi nationals are complicit in supplying regimes with technical support. Tom Watson noted that the “Internet is a neutral tool that can be used for good and bad”. Watson suggests that democracies should attempt to restrict China and other totalitarian regimes access to communication technologies. While Twitter and Face Book has been used in Iran as technologies of opposition and change, we have also seen repressive regimes use the Internet as a technology of control to monitor dissent.

Sources:

Davies, Simon Big Brother: Britain's web of surveillance and the new technological order London: Pan, 1997

Donk, Wim van de (ed.), foreword by Peter Dahlgren Cyberprotest: new media, citizens and social movements, London New York: Routledge, 2004

Lyon, David, Surveillance society: monitoring everyday life Buckingham: Open University Press, 2001

McCaughey, Martha & Ayers Michael D. (ed.) Cyberactivism: online activism in theory and practice, New York London: Routledge, 2003

Meikle, G Future active: media activism and the internet New York London: Routledge, 2002

Web resources:

Robert Amsterdam, a lawyer specialising in cases against repressive governments, and Tom Watson MP, a prominent blogger who has tabled an Early Day Motion on the Google-China issue, discuss how the internet is used by rogue governments. Today: Thursday 21st January 0835: http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_8471000/8471658.stm

BBC News: “China Blocking Google” http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/2231101.stm

“Google censors itself for China”: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/4645596.stm

“Web inventor warns of 'dark' net” By Jonathan Fildes: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/5009250.stm

“Berners-Lee on the read/write web”: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/4132752.stm

Listen to "Web inventor's future fears": 'The British developer of the world wide web says he is worried about the way it could be used to spread "misinformation".' Professor Sir Tim Berners-Lee spoke to Pallab Ghosh on BBC Radio 4's Today programme. 2 Nov 2006

“Defending online freedom” Guardian Online:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/libertycentral/2010/jan/22/hillary-clinton-online-freedom#start-of-comments

Wired Online: “China Restores Google.com”: www.wired.com/news/politics/0,71121-0.html

Culture and Communication

I have in previous posts discussed the Internet and the World Wide Web as communication tools and as social condensers. From Soviet constructivist theory, the social condenser is a spatial idea practiced in architecture. Central to the idea of the social condenser is the premise that architecture has the ability to influence social behaviour (as discussed in Shock of the New episode 4, “Trouble in Utopia”). It may be argued that the ‘architecture’ of the WWW, a ‘public space’, breaks down perceived social hierarchies and creates an environment that allows and encourages disparate groups and communities to interact. We can explore how real and virtual communities formed and sustained. In 1997 Microsoft set up a project: ‘MSN Street’ in which the residents of a North London road were given computers and free access to the Internet.

These communication technologies can impact on communities in many different ways. In the rural Western Isles of Scotland, this communication technology is used to keep traditional communities together. It also helps to develop new communities: today we may think of My Space or Second Life amongst many others.

Tom Standage the author of The Victorian Internet (1998), points to the features common to both the telegraph networks of the 19th Century and today’s Internet (Standage was on the reading list for Week one of Media Technologies and Public spheres). He compares them both in terms of the speed of communication, their commercial possibilities, the utopian notion of connectivity and the transcendence of national and political boundaries. These viewpoints are not too dissimilar to Marshall McLuhan’s (1911-80) claim that the new electronic media would restore our sense of community and collectivity creating what he called a ‘global village’.

However communication is not simply about information, surely? Is it not about social grooming and our increasing ability to talk might not have been (or should that be just been?)about helping one another understand the world, but a guard against lying.

Further reading:

Bell, David J. [et al.], Cyberculture: the key concepts London: Routledge, 2004 303.4834 bel

Kiesler, Sara (ed) Culture of the Internet Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1997

Nayar, Pramod K. Virtual worlds: culture and politics in the age of cybertechnology

New Delhi London Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2004

O’Sullivan, T et al, Key Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies London: Routledge, 1994 2002

Preece, Jenny, Online communities: designing usability, supporting sociability New York: Wiley, 2000 e

Spender, Dale Nattering on the net: women, power and cyberspace North Melbourne: Spinifex, 1995

Websites:

Tom Standage’s Home Page: www.tomstandage.com

Ross Bleckner: 3

Ross Bleckner at Mary Boone, NYC (February 2010)

Originally uploaded by ballenato63 on Feb 17, 2010

Damn those Computers (and other things)!

Cyberculture to E-Culture (sounds so late eighties early 90s)? Erm... Towards E-topia? Part 2

In the mid to late nineties we saw the struggle between Netscape and Microsoft for control of the Web. Controlling the means of communication controls the information that flows through it. Companies like Reuters have always appreciated the importance of technology in the distribution of information. Microsoft attempted to create an alternative web with MSN (Microsoft Network). This essentially failed. The creation of Explorer, Microsoft’s browser, challenged the dominance of Netscape. This led to disagreements over technical protocols and certainly Microsoft’s early actions have been interpreted as an attempt to curtail the freedom of the user and the eclectic and anarchic nature of the web, with Microsoft pushing it’s own ideas about protocols that were/are different from everyone else’s. These technical difficulties have been largely resolved through the dedication of people like Tim Berners-Lee and the World Wide Web Consortium (www.w3.org). Microsoft’s business practices have been questioned and it’s monopoly of the operating system and web browser market that has in the words of some commentators led to a monoculture, has been attacked in court. This did not lead to a break up of the company, but recently Mozilla Firefox has challenged Microsoft’s dominance of the browser market.

New Scientist: “Microsoft monoculture allows virus spread” 25 September 2003: www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn4203

Cyberculture to E-Culture (sounds so late eighties early 90s)? Erm... Towards E-topia? Part 1

There is another invention that radically changed European culture and politics, an ‘ancestor’ of the WWW: the European technology of printing and moveable type, in the 15th Century by Johannes Gutenberg. This technology was a key development in the Renaissance and became a major factor in the Reformation. To those privileged to read (remember most Europeans of the fifteenth century were illiterate), all world knowledge in the west resided in two sets of texts: The Bible and the works of Aristotle. Today, we throw the equivalent amount of information into the recycling bin after we have finished with our Sunday newspaper. How many words exist on the WWW? It is also important to note that in the 15th Century ‘our’ main source of information came from village gossip, art and the pulpit.

Tim Berners-Lee, the ‘inventor’ of the web and the HTML code (of course he had a little help from Ted Nelson who devised hypertext), has on a number of occasions explained his role as inventor and as an observer and commentator of its use and rapid expansion. The Internet was initially invented the 1960s, a product of the military-industrial complex to allow scientists and the military to share information and maintain communications in the event of a nuclear attack. Post cold war, from being a tool of largely governmental agencies the Internet quickly became a global network.

The idea of a global network of easily accessible information is a product of liberal capitalism and a democratic society. These inventions have created a virtual soapbox, where theoretically everyone has the right to publish: a right to free speech. Tony Benn the ex-labour MP, sees the Internet/WWW as something that is beyond the control of governments. However, since many sites are unedited there is the threat of misinformation and for the potential circulation of dangerous ideas.

Cyberhistories: Cyberspace, Cyber Art and Cyberculture

Postwar we see digital pioneers from John and James Whitney to Benoit Mandelbrot. Computers can be seen as a creative and liberating force, a seductive and progressive idea reinforced by advertising campaigns that promote software such as Photoshop and hardware like the Apple Mac computer. Look at the way Apple promoted the Mackintosh computer. Generally, we see a shift from computers being viewed as part of a culture of calculation (as parodied by Rube Goldberg and Heath Robinson), seen in the examples of the machines designed by Charles Babbage or seen in Bletchley Park in WWII, and stereotypically PCs and Unix and command line environments, subject to hierarchy and centralised control (a tendency of Modernism) to one that includes the Internet and the WWW and emphasises a culture of simulation that is decentralised and fragmented (a tendency of Post-Modernism). The more recent digital and interactive design of John Maybury, Jenny Boulter and William Latham will bare witness to this ‘liberation’, as they themselves reveal the blurring distinctions between design practitioners and their practices and computer science. These are just of few of the professionals who have shaped the use of this fairly new medium, influenced art and designers and experimented and stretched the creative potential of these technologies.

Plato's Cave

Book VII of The Republic

The Republic

Written 360 B.C.E

The Allegory of the Cave

[Socrates is speaking with Glaucon]

[Socrates:] And now, I said, let me show in a figure how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened: --Behold! human beings living in a underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.

[Glaucon:] I see.

And do you see, I said, men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent.

You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners.

Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave?

True, he said; how could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?

And of the objects which are being carried in like manner they would only see the shadows?

Yes, he said.

And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them?

Very true.

And suppose further that the prison had an echo which came from the other side, would they not be sure to fancy when one of the passers-by spoke that the voice which they heard came from the passing shadow?

No question, he replied.

To them, I said, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.

That is certain.

And now look again, and see what will naturally follow if the prisoners are released and disabused of their error. At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows; and then conceive some one saying to him, that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clearer vision, -what will be his reply? And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them, -- will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?

Far truer.

And if he is compelled to look straight at the light, will he not have a pain in his eyes which will make him turn away to take and take in the objects of vision which he can see, and which he will conceive to be in reality clearer than the things which are now being shown to him?

True, he said.

And suppose once more, that he is reluctantly dragged up a steep and rugged ascent, and held fast until he 's forced into the presence of the sun himself, is he not likely to be pained and irritated? When he approaches the light his eyes will be dazzled, and he will not be able to see anything at all of what are now called realities.

Not all in a moment, he said.

He will require to grow accustomed to the sight of the upper world. And first he will see the shadows best, next the reflections of men and other objects in the water, and then the objects themselves; then he will gaze upon the light of the moon and the stars and the spangled heaven; and he will see the sky and the stars by night better than the sun or the light of the sun by day?

Certainly.

Last of he will be able to see the sun, and not mere reflections of him in the water, but he will see him in his own proper place, and not in another; and he will contemplate him as he is.

Certainly.

He will then proceed to argue that this is he who gives the season and the years, and is the guardian of all that is in the visible world, and in a certain way the cause of all things which he and his fellows have been accustomed to behold?

Clearly, he said, he would first see the sun and then reason about him.

And when he remembered his old habitation, and the wisdom of the den and his fellow-prisoners, do you not suppose that he would felicitate himself on the change, and pity them?

Certainly, he would.

And if they were in the habit of conferring honours among themselves on those who were quickest to observe the passing shadows and to remark which of them went before, and which followed after, and which were together; and who were therefore best able to draw conclusions as to the future, do you think that he would care for such honours and glories, or envy the possessors of them? Would he not say with Homer,

Better to be the poor servant of a poor master, and to endure anything, rather than think as they do and live after their manner?

Yes, he said, I think that he would rather suffer anything than entertain these false notions and live in this miserable manner.

Imagine once more, I said, such an one coming suddenly out of the sun to be replaced in his old situation; would he not be certain to have his eyes full of darkness?

To be sure, he said.

And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady (and the time which would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be very considerable) would he not be ridiculous? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one tried to loose another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.

No question, he said.

This entire allegory, I said, you may now append, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument; the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief, which, at your desire, I have expressed whether rightly or wrongly God knows. But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort; and, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right, parent of light and of the lord of light in this visible world, and the immediate source of reason and truth in the intellectual; and that this is the power upon which he who would act rationally, either in public or private life must have his eye fixed.

Weblinks

Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality: About the book

Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality: The Companion Website

The Virtual Revolution: The BBC 2 Series

Saturday 20 February 2010

Max Ernst: 4

"Max Ernst and the Surrealist Revolution", Part 3.

Max Ernst: 3

"Max Ernst and the Surrealist Revolution", Part 2.

Max Ernst: 2

Friday 19 February 2010

Gerhard Richter

My own experience of Richter’s work is rather limited outside of books and other reproductions. I recall that sometime between 1988-1991 Richter’s name came to my attention, firstly in the art classes and then in the studios and at college: West Park and then Stourbridge. His work was very visible. Richter’s Kerze (Candle) 1983, featured on the cover of Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation (Kerze, 1982 featured on the inside cover). Richter seemed the height of cool.

Betty 1988

The early Richter’s are smudgy, smudgy like old news print photographs. “Richter like Andy Warhol appropriated tabloid as well as snapshots” in an attempt to reconnect “his art to the contemporary social world” (Wheeler, 1991 p279). The end result is “deadpan, hands-off” (1991, p. 279). The effects are similar to those in Photoshop as it fuses together the techniques of photography and the visual effects of oil paint. These kinds of effects can be achieved very easily within that programme. The qualities of paint within Richter’s work is very interesting: “whether in full colour or monochrome sepia , the image might be delicately glazed and scumbled to suggest timeless candlelight moment or its surface smudged and dragged to create an impression of a flash in the torrent of media images” (Wheeler, 1991 p.279).

Sources:

Nasgaard, R., (1988) “Gerhard Richter: The Figurative work” in Neef, T,. (ed) (1988) Gerhard Richter: Paintings, London: Thames and Hudson pp.39-72.

Neef, T,. (ed) (1988) Gerhard Richter: Paintings, London: Thames and Hudson.

Wheeler, D. (1991) Art since Mid-Century: 1945 to the Present, London: Thames and Hudson.

Anselm Kiefer

Kiefer’s subject is Germany’s past. The heavy weight of history is incredible. A Kiefer composition can draw upon Goethe’s Faust and the Old Testament’s Song of Solomon. Margarethe (1981) and Shulemith (1983) both make reference to the Old Testament and Paul Celan’s Death Fugue, a Holocaust memorial:

Paul Celan: Death Fugue

Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown

we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night

we drink it and drink it

we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents

he writes he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

he writes it and steps out of doors and the stars are flashing he whistles his pack out

he whistles his Jews out in earth has them dig for a grave

he commands us strike up for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you in the morning at noon we drink you at sundown

we drink and we drink you

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined

He calls out jab deeper into the earth you lot you others sing now and play

he grabs at the iron in his belt he waves it his eyes are blue

jab deeper you lot with your spades you others play on for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at at noon in the morning we drink you at sundown

we drink and we drink you

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith he plays with the serpents

He calls out more sweetly play death death is a master from Germany

he calls out more darkly now stroke your strings then as smoke you will rise into air

then a grave you will have in the clouds there one lies unconfined

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at noon death is a master from Germany

we drink you at sundown and in the morning we drink and we drink

you death is a master from Germany his eyes are blue

he strikes you with leaden bullets his aim is true

a man lives in the house your golden hair Margarete

he sets his pack on to us he grants us a grave in the air

He plays with the serpents and daydreams death is a master from Germany

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith

(N.B. some texts spell “Shulamith” as “Sulamith”; I am assuming that this is incorrect).

Margarete is the blonde personification of Aryan womanhood while Shulamith is the sybol of Jewish womanhood. For the painting Shulamith, Kiefer appropriated Wilhelm Kries’ Funeral Hall for Nazi war heroes, built in 1939 to create a blackened crypt: a Nazi monument becomes a Jewish one.

Kiefer has been posted here because of his mixed-media approach and his ability to fuse an all-overness design into his paintings similar to Pollock with a politically engaged message. Peter Schjeldahl wrote that Kiefer had “thoroughly assimilated and advanced the eshetic lessons of Jackson Pollock’s doubleness of special illusion and material literalness on a scale not just big, but exploded, enveloping, discomposed” (Wheeler, 1991 p.314).

Hughes, R., (1991) The Shock of the New, London: Thames and Hudson.

Wheeler, D., (1991) Art Since Mid Century New York and London: Thames and Hudson.

Thursday 18 February 2010

Malcolm LeGrice

Malcolm Le Grice's Berlin Horse /

Sound by Brian Eno

" Multi-projection film Berlin Horse (1970) was based entirely on a novel but simple idea of a repeating, subtly changing film loop. The soundtrack created by Brian Eno was also implemented using a tape loop. According to the director, Berlin Horse examines how the eye works and how the minds builds up a perceptual rhythmic structure" (From YouTube).

Wednesday 17 February 2010

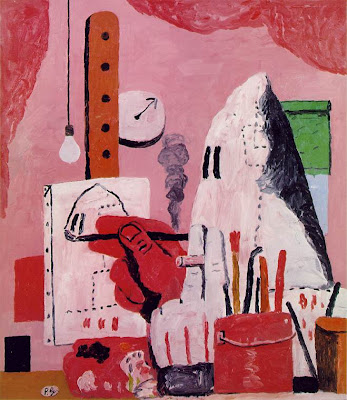

Philip Guston

Mother and Child, 1930.

Conspirators 1932.

Porch No 2 1947

Tormentors 1947-48

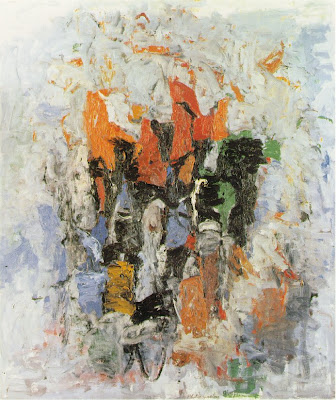

Review 1948-50

In the fifties we see Guston “resolve his divergent tendencies (Wheeler, 1991, p. 58) and “purified his paintings” (O’Hara, 1975 p. 136). The dialogues with de Chirico and Giavanni di Paola disappear – and we see the more abstract tendencies of the paintings of Cezanne and Tiepolo, Turner and Impressionism. Paintings like B.T.W and Zone are made up of shimmering painted strokes, horizontal and vertical dashes making up pluses and minuses: a Mondrian reinterpreted by Monet. The paintings of the fifties do resemble parts of Monet’s Waterlillies: The Irises 1916-23, although Frank O’Hara does say “not late Monet” (1975 p.136). This argument is also supported by Robert Hughes who sees a closer relationship between Guston's abstractions and Mondrian's seascapes he painted on the coast of Schveningen in 1912-15 (1997, p. 584).

B.T.W. 1951

B.T.W. 1951 Zone 1953-54

Zone 1953-54

The Clock 1956-57

In the sixties the tones darken and the imagery seems unresolved. In the late sixties during a period of political and social upheaval “unexpectedly”, David Anfam recalls “he (Guston) halted the palimpsest compositions which had grown greyed and more monumental by the early 1960s and instead wretched to the surface scenes that they had seemed to cloak” (Anfam, 1999, p.207). Guston in his explanation of “his departure from high-minded formalism… said simply ‘I got sick and tired of that purity. Wanted to tell stories’” (Wheeler, 1991 p.290). The New York Times critic Hilton Kramer called Guston “a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum” – he was wrong. Guston brought into his paintings his earlier anti-fascist concerns, fusing it with the language of comics and cartoons. This time the Klansmen are bumbling, bullying buffoons of the Nixon years.

Close-up III 1961

City Limits 1969

Daniel Wheeler explains the reasons for this strategy by reminding us that “just as the Baroque had unfolded in the shadow of the High Renaissance, late modernism as a whole, as well as post-minimalism in specific, found itself struggling with the after effects of a glorious past, a modernist past whose revolutions had produced not Utopia, but instead a society shot through with grotesque incongruities, political, economic and aesthetic” (Wheeler, 1991, p.290). Guston’s response was to reclaim the art of his idealistic past and produce once again a humanist art.

The Studio 1969

Why add Guston to this blog anyway? Well, mainly because of his struggle as an artist and the need to recognise the unresolved struggle between the idealistic, the political and a convincing aesthetic that is fully resolved and sustainable.

Anfam, D., (1999) Abstract Expressionism New York and London: Thames and Hudson

Hughes, R., (1997) American Visions The Epic History of Art in America London: Harvill Press

O’Hara, F., (1975) Art Chronicles 1954-1966, New York: A Venture Book, George Braziller Inc.

Wheeler, D., (1991) Art Since Mid Century New York and London: Thames and Hudson.

Robert Motherwell

Although an abstract painter, Motherwell’s work “constantly reaches out into life”: his Elegies

working as “general metaphors of the contrast between life and death and their interrelation" (Lynton, N., 2003 p. 243).

In Plato's Cave No. 1 1972

In Plato's Cave No. 1 1972

Summer Open with Mediterranean Blue 1974

Summer Open with Mediterranean Blue 1974Lynton, N., (2003) The Story of Modern Art, London and New York: Phaidon.

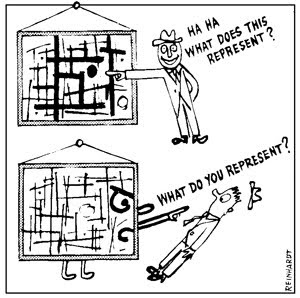

Ad Reinhardt

Reinhardt’s art “moved from geometrical abstraction through a controlled and markedly impersonal form of Abstract Expressionism into a uniquely concentrated and super elegant geometrical abstraction. From 1960 until his death in 1967 he painted nothing but square canvases of one size in which two barely distinguishable coats of black present a cruciform trisection of the surface” (Lynton, N., 2003, p.244).

Abstract Painting No. 5 1962

Abstract Painting No. 5 1962Ad Reinhardt in his essay “Art as Art” argued against art-as-expression or art-as-apocalypse. “Art”, he argued “needs no justification with ‘realism’ or ‘naturalism,’ ‘regionalism’ or ‘nationalism,’ individualism’ or ‘socialism,’ or any other ideas” (Reinhardt, A., 1992 p.806). “The one standard in art”, he suggests “is oneness and fineness, rightness and purity, abstractness and evanescence. The one thing to say about art is its breathlessness, lifelessness, deathlessness, contentlessness, formlessness, spacelessness and timelessness. This is always the end of art” (Reinhardt, A., 1992 p.806).

Sources:

Harrison, C. and Wood, P., (1992) Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford: Blackwells.

Lynton, N., (2003) The Story of Modern Art, London and New York: Phaidon

Reinhardt, Ad (1962) "Art as Art" in Harrison, C. and Wood, P., (1992) Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford: Blackwells, pp.806-809.

Daro Montag

''Radiance III' 1994

''Radiance III' 1994Ilfachrome print from 35mm slide

Ilfachrome print from 35mm slide

paper, 24" x 24,"

paper, 24" x 24,"

Tuesday 16 February 2010

Current Developments 5

The painted surafaces fuse with photographic imagary from screens depicting trees and natural forms.

The imagery draws upon a wealth of technologies and there histories. There is solarization, photogram and negative imagery. Slight modulation in opacity of one layer of imagery can have a profound effect on the image as a whole.

Solarization, light bursts and a silvery colour add to a kind of nostalgia or longing that is provoked by the medium of photography.

Pattern of seeds of dandelion? or milkweed? Photographic engraving, mid 1850s.

Pattern of seeds of dandelion? or milkweed? Photographic engraving, mid 1850s.